Rambu Solo’ is a series ceremonies for the dead, and is also called Allu Rampe Matampu’ meaning Ritual of the west, the direction which is connected with death.

Death is a sad event but for the people of Toraja it is also an occasion for happiness, a celebration of the passage of the soulk to puya, the

The most important ceremony in the life of Torajans, Rambu Solo’ is a series of ceremonies celebrated by the kinship group and participated by the community in a festive atmosphere.

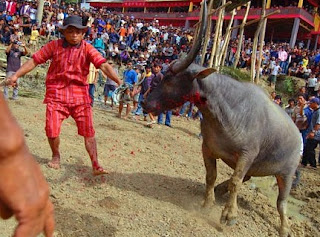

There are several types of funeral ceremonies depending on the status of the dead, his or her social class and wealth, as well as the area. The higher the castle, the more elaborate are the ceremonies. Those of the lowest tana’ kua-kuatana’ bulaan hold two different rituals and sacrifi many buffaloes and pigs. The ceremonies last several days and they are highly publicized and attract many visitors to the area. or slave class, have very simple rituals while the nobility

Since the many offerings received help the soul of the dead to reach the status of deity, the funeral ceremonies can be very expensive to the family and it can take place months or years after death.

The ranbu solo’ besides providing for the soul of the dead, is meant to signify the social status of the family and is an opportunity to repay favous and gifts received by the dead person during his or her lifetime. One most important function of these ceremonies is the division of the inheritance, for whoever, son or daughter, contributes the most buffaloes for the sacrifice at the funeral feast, he or she is entitled to a greater share of the inheritance.

As wealth and power are needed to reach Puja, Torajans aspirate to accumulate wealth and power during their lifetime so that they can hold a death ritual befitting their status.

Accrding to Toraja beliefs, a dead person is considered a sick person until the death rituals begin. Called tomasaki ulunna, meaning one whose hesd sick, the corpse is kept in the special place in the house reserved for that purpose. Meanwhile. The soul departs through the head and wanders in the village. Still the dead is regarded as asick person and is treated as such and laid with the head to the west. Meals are placed by the side of the corpse, and neighbours and relatives came calling, bringing betel nuts and tobacco.

There is nothing unusual about the family sleeping in the same rooms as a corpse. Any decaying smell is ignored althougth now there are more cases of embalming or enclosing the body in a temporary coffin, with a bamboo cylinder extending from it like a narrow chimney to carry the smell out of the house.

This is the time for the funeral prepations and the kinship group start to save money and collect rice for the death ritual. It is scheduled when all relatives can be a matter of days, weeks, months and even years.

The “sick” person becomes tomate really ead when the rituals begin. On the ma’karu’ dusun day, sacrifice of a buffalo indicates the real death. Its innards are cooked in a bamboo container and offered with palm wine to the dead.

From this day, the relatives start their mourning, eating no meat or rice. The body is moved from the southern room to the centre room and laid wuth the head pointing south. As this is a position for the dead, it is taboo for the living to sleep with their heads pointing south.

For the nobility, this is the first ritual for the dead and can last for seven days. Many buffaloes and pigs are sacrifieced and the corpse is symbolically wrapped and put into a temporary bangka, coffin, hich is then placed in the the western part of the Sali or centre room.

Some tme passed befor the second rituals is held. Preparations include the construction of temporary houses around the rante or ceremonial field. A simbuang batu, ceremonial stone and palm tree are erected as aplace to tie the buffaloes, a bala kayan, meat tower and lakkian, a tower for the dead in the shape a tongkonan house are built.

When all is ready, the corpse is taken out of the temporary coffin, and is hung for a few days from the ceiling of the house before being removed to the base of the rice barn, opposite the house. Here it is wrapped in a decorative funerary sack by the death priest.

Then it is time for the funeral procession with the wrapped corpse carried in Tongkonan-shaped bier with widow or widower following in a chair covered with a black canopy. The effigy made in the image of the ded, is accompanied by gong beaters, war dances and buffaloes. The mouerners dressed in black, hold a red length of cloth, which extends from the bier, over their heads.